![]()

According to Flitney

and Brown [1], a labyrinth seal operates on following two methodologies:

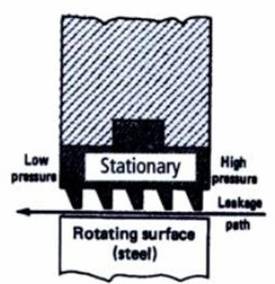

rotating radial faces cause centrifugal separation of

liquid or solid from air and a series of restrictions followed by a clear

volume creates expansion of a gas and hence reduces the pressure. These seals

use a very small gap in between the seal and the rotating shaft, and then grooves

are machined into the seal in order to disrupt the flow. A general design of a

labyrinth seal is shown in figure 1 [2]. The fluid is prevented from leaking

through the seal by the grooves which induce turbulence and misdirect the flow

into the small gaps between each tooth. According to Boyce [2], a labyrinth

seal has the following advantages: simplicity, reliability, tolerance to dirt,

system adaptability, very low shaft power consumptions, material selection

flexibility, minimal effect on rotor dynamics, back diffusion reduction,

integration of pressure, lack of pressure limitations, and tolerance to gross

thermal variations. Boyce [2]

further claims disadvantages associated with this type of seal are the following:

high leakage, loss of machine efficiency, increased buffering costs, tolerance

to ingestion of particulates with resulting damage to other critical items such

as bearings, the possibility of the cavity clogging due to low gas velocities

or back diffusion, and the inability to provide a simple seal systems that

meets OSHA or EPA standards.

There are several variations of the generic

seal design (discussed above) currently in use at Danfoss

- Turbocor.

The designs vary in tooth number, tooth size and spacing, step number,

and sizing. Much research has been preformed regarding the labyrinth seal designs, however engineers at Danfoss-Turbocor

are uncertain as to what combination of variants will produce the least amount

of leakage through the seal.

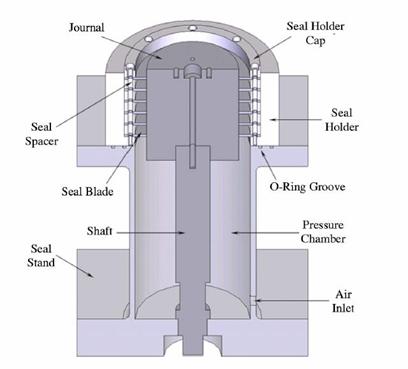

An experiment was

conducted at

Figure 2: Test Rig used in the